I remember writing the comments that I was asked about. I remember it very well. I remember where I was sitting and what the weather was like. I also remember the cloud that my consciousness was in when I typed those statements.

At the time, I was still very much under the malicious influence of lies and distortions that is almost unavoidable in modern Miami.

Many - if not all - of the statements I made about Fidel Castro and race were influenced by my experiences growing up in one of the most bigoted communities ever known to one of the most bigoted countries history has ever known. I have always tried to say - here in this country supposedly built upon the free and respectful exchange of ideas, opinions, and experiences - that Cuban racism is every bit as virulent as what humanity saw in South Carolina in the 1820's, Mississippi in the 1950's, South Africa in the 1970's, and Washington, D.C. from 1789 to present. I naively thought it only natural that a white Cuban in Cuba would be just as racist as the white Cubans I knew in Miami.

Thus was my narrow-minded lack of consciousness when I read Castro, the Blacks and Africa by Carlos Moore. Moore was the man that translated for Fidel Castro during the Cuban leader's legendary visit to Harlem and the Theresa Hotel in September, 1960.

I was primed for the misrepresentations contained therein and I swallowed them all and passed them along in the only manner one can pass along that which has been swallowed: with the foul stench of intestinal refuse.

Growing up in Cuban Miami during the 1970's and early 1980's, I was taught like other Cuban-American children in South Florida a distinct and dysfunctional version of the old American adage "If you don't have something nice to say about someone, don't say anything at all." The way that saying works in the ultra-rightist, reactionary, intolerant den of democratic inequity is as follows:

"If you don't have something nasty and hateful to say about Fidel Castro, don't say anything at all."

Anything else can run one the very real risk of being branded a Fidelista. That is a very serious concern in a community that openly and proudly harbors several anti-Castro terrorist organizations and, thus, has a history of bombings and the like.My worldview was tinted by that dogmatic brain-washing (heavy on the bleach) until 26 March, 2000 when I had the good fortune of encountering the indomitable Dr. Alberto Jones, a generous Guantanamero, in the historic chapel of my alma mater.

Dr. Jones is a fascinating man whose energy belies his actual age. A defiantly and politely proud patriot, he also takes great pride in his Jamaican ancestry. I have taken great pride in passing along quite a few of Dr. Jones' columns and essays over the years.

Among the things I am grateful for about our friendship, the one thing that stands out the most is the opening of what is an ever-increasing devotion to freethinking and truth seeking.

A price tag cannot ever be put on that gift and I will be ever grateful for it.

The times when I have heard an African-American express any opinion about Fidel Castro, most of the time, the opinion that is expressed is one based on that individual’s perception of a certain significant level of respect he or she has for the Cuban leader. This perception of Castro is often muddied by the incessant and confusing demonizing of him and his initiatives as practiced by both this country’s corporate media and successive administrations in Washington, D.C. Thus, the question that logically follows is “what are we missing about Castro when it comes to skin color?”

To get a good idea about the degree to which one’s view of Castro "as a person whose feelings towards" African-Americans and humanity as a whole is justified, I suggest going straight to the horse's mouth.

The easiest way to do that is to refer to his speeches.

It is easy to demonize someone that one doesn't allow others to hear. Of course, that is if the person one is trying to demonize is not a demon (conversely, the best way to demonize an actual "demon" is to just let him/her talk with an audience).

The more and more I read what I can find of Castro's writings and oratory, the more I can see why there are so many people (most of whom are outside of the stifling influence of U.S. corporate-owned media) that - at minimum - respect him and - at other degrees - practically idolize him.

Living in this country, I have relatively little access to Castro’s speeches but the transcripts from a speech to the United Nations in 1979 on behalf of the Non-Aligned Movement; a speech given in Kingston in 1998; and his legendary courtroom obra maestra from the 1950’s that is better known by its closing line, “History Will Absolve Me” are works I have been impressed by.

The current revolution that Castro has led is a throwback to the original Cuban Revolution of the 19th century. This revolutionary struggle was quite unique and, by all accounts I am currently aware of, the first of its kind in that its philosophical framework stressed the importance of being a struggle that transcended the artificial and fictious constructs of racial and ethnic divides. In fact, racism was considered to be "unpatriotic" (although too many instances of "unpatriotic" acts and attitudes hobbled the revolution in many instances). This revolution also maintained that, as José Martí wrote, "exclusive wealth is unfair."

The beginnings of this struggle are also interesting to note. When an American is asked, "What do you celebrate on the Fourth of July?" the indoctrinated response is "INDEPENDENCE DAY!" (It is this writer’s hope that Americans familiar with Frederick Douglass’ famous views on this “holiday” will appreciate what follows).

Every American school child is taught that the Declaration of Independence was written by Thomas Jefferson whom every American school child is asked to forget was a slave-holding aristocrat.

If the same standard is applied to Cuba, then Cuba's Independence Day is October 10th, 1868.

On that warm autumn day near the eastern Cuban city of Bayamo, slave-holding plantation owner Carlos Manuel de Cespedes had the bell at the Big House rung in the tradition of all slave cultures in the Americas to summon everyone to hear some big announcement. That "big announcement" was that, from that day forward, Cuba would be a free and sovereign nation and, since no nation could be free so long as any of its children was enslaved, de Cespedes instantly emancipated the human beings that he previously held as property.

Thus, the Cuban revolution accomplished in one moment what the American and French revolutions failed to do - largely because the latter pair chose not to do. While Jefferson wrote that "all men are created equal" and Lafayette suggested a Universal Rights of Man, de Cespedes actually put into irrevocable action the very same ideas that the very laws of humanity demand.

As one can see, the parallels between the American and Cuban revolutions end rather quickly.

October, 1868 set into motion what became the definitive and defiant anomaly of the Victorian Age. While Europe and the United States were putting the macabre and sadistic tenets of social Darwinism (the "scientific paradigm" that was in vogue at that time among learned and civilized men of culture - read that to mean white men – which spoke so self-righteously of superior races and inferior races designed to justify modern colonialism) into brutal and avaricious practice in Africa and Asia and western North America, Cuban revolutionaries set out to drive Spain (the originator of the various modus operandi of modern colonialism) into the Caribbean Sea.

There were no more master and slave - only citizens. To be racist was to be unpatriotic - a traitor to the homeland. Black, white, Cantonese, and mixed-race Cubans rose in righteous rebellion against the Spanish crown and all of the oppressive and dysfunctional institutions it so callously imposed upon Cuba. As was said during the thirty-year struggle for independence, the blood of both white and black patriots spilled on the field of battle fighting for Cuba intermingled to fertilize the soil of freedom.

To have a revolutionary ideology (that at times manifested itself almost as a radical theology) which not only spoke and wrote of the brotherhood of all humans but also acted upon it (over 70% of the officer corps of the Army of Independence was "of color") was something that ran in the face of all that was reassuring to Euro-centric concentrations of political, economic, social, and military power.

This war of independence was fought on and off for the next thirty years after the “Grito de Yara” in October of 1868 (just three years and a few hundred miles removed from Paul Bogle’s march on the court house in Morant Bay).

This takes us back the question posed the prompted this humble answer.

For Castro and many Cubans on and off the island, the current revolution is a continuation of that first struggle to throw off the suffocating chains of colonialism for the improvement of life for all Cubans.

To get a better idea about the degree to which one’s view of Castro "as a person whose feelings towards" humanity as a whole is justified, I suggest going straight to the path of the horse's hoofprints.

The best way to do that is to refer to Cuba’s policies, programs, and actions.

Dr. Jones has written that Cuba has produced more Black doctors in the past forty years than Jamaica has in four hundred years.

Cuba also trains - for free - medical students from Haiti, Sub-Saharan Africa, and Latin America.

The only "catch" is that graduates do not go back to their homes to buy a garage full of Mercedes Benz' but, instead, work according to the Hippocratic Oath to heal people for the sake of healing.

This offer has been extended to African-American students and has been on the table for years. Naturally, very few in this country have taken advantage of this opportunity because very few in this country are aware of it (one notable exception is Cedric Edwards, a native of Slidell, Louisiana who just completed the program, making him the first African-American to do so).

The lessons for Americans should be apparent. So should the possibilities.

To get a better feel for the lessons and the possibilities, let us examine the “post-colonial” Caribbean reality that begat the ongoing current chapter of the Cuban revolution.

Fulgencio Batista was another manifestation of that sad Latin American institution of the caudillo or strong man, the Banana Republic thug who was able to hold onto his impoverished fiefdom in the Yankee empire largely via the support of American business interests.

Research Latin American history after the economic and military rise of the United States and one will find a wide array of degenerates with one thing in common: they stayed in power for as long as they were on good terms with United Fruit, Dole, Hershey, et al.

With the triumph of the Bolshevik Revolution in Russia and the subsequent attention given to growing left-of-center economic and political movements in the world, the United States found a justification for supporting blatantly brutal dictatorships in its own tranquil backyard oasis bereft of democratic values and traditions. While the American people were being told that these regimes were anti-communist at a time when anything red was automatically connected directly with the forces of evil, the reality of U.S. rationale behind the protection of these tyrannies was phrased best by Franklin Roosevelt in his assessment of the Dominican Republic's longtime despot Rafael Trujillo:

"He may be a son-of-a-ibtch but he's our son-of-a-itbch!"

That infamous statement of rare American political frankness can easily be applied to miscreants such as Ubico in Guatemala, Pérez Jimenez in Venezuela, Somoza in Nicaragua, Strossner in Paraguay, Machado in Cuba, Duvalier in Haiti just to name but the more notorious.

Batista, like many of the other caudillos in Latin America, actually bore the mantle of progressive redeemer when he ousted the cruel Gerardo Machado, a butcher described by Time magazine on its cover as "The Cuban Mussolini." The realities, however, of the old maxim that says POWER CORRUPTS soon kicked into gear and Batista started earning comparisons between him and the man he sent into exile in the early 1930's.

Batista personally invited the American Mafia vis-à-vis Meyer Lansky (the Jewish Godfather) to overhaul the casinos in Havana. If vice was easy to come by in Cuba before, it soon became almost inescapable as contemporary accounts of the period seem to universally state that anything could be bought in Havana. Thus, Cuba became a giant floating whorehouse seemingly existing only to cater to every perversion imaginable to Americans of every ilk and persuasion.

The de facto brothel status of Cuba did not only apply to casinos and bars and houses of ill repute. Most of the infrastructure of Cuba's bustling economy was foreign-owned and/or -operated - mostly by American corporate interests. The vital utilities (telephone, electricity), the rail lines, the arable soil, et al was in the firm control of American-owned (and Defense and State Department-protected) transnationals.

Since Cuba was operating as a modern plantation, it served that not only the absentee landowners reaped egregious financial benefits but also a trusted elite of natives made small fortunes as well. Indeed, on this plantation, the house Negro was not only relatively affluent but he was (thanks to the dysfunctional complexities of Spanish racism in Cuba) also genuinely white.

Naturally, even the most impressive profit margins ultimately are finite and avarice will only allow for so much wealth to be "shared." So, as is always the case on any plantation, there was literally nothing left to give to those whose efforts generated the huge chunks of black in the ledgers but the monetarily worthless commodities of grief and misery.

From Dr. Jones:

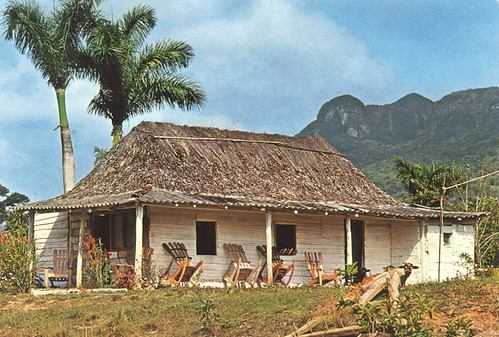

In this community on the "other" side of the tracks, I learned early on, that the only homes we were allowed to build were the shack-type homes with thatched roofs that defined our living quarters. Sewer, running water, electricity, schools, jobs, hospital or medical services were limited to people living on the "other" side of town.

What we did have was a pervasive infant mortality due primarily to preventable diseases that touched the lives of every family. There were rampant pre and post partum deaths; hunger and malnutrition seen predominantly in children with their disproportionate heads and distended abdomens, overflowing with such a variety of intestinal parasites sufficient to produce our own Atlas of Parasitology. Another common landmark was the infamous gully with its putrid drainage winding through our neighborhood.

The only schools in our community of approximately 8-10,000 people, were two or three mock-classrooms of 10-20 children in the living room of those slightly more enlightened members of our community.

Two churches had what could be qualified as small schools, with approximately 40 children each. Because of our teachers’ own limited education, the level of training by those who were able to stay through the entire school program (3-4 years) was the equivalent of a low third grade.

Unbelievable as it may sound today, most of the kids could not stay in school, either because their parents could not afford it or their helping hands were already required on the plantation. As a direct result of this horrendous environment, our community, and tens of similar ones dispersed through what was then the provinces of Camaguey and Oriente, did not produce in 60 years a single person who had achieved a mid level or higher education. An exception was a lady who was able to complete nursing school, only because her parents had the vision and could afford to send her back to Jamaica.

The only jobs available was in the zafra, the 4-5 months sugar harvest, which was virtually slave labor, because it was not only the lowest paying job, but it also kept the people in perennial debts: whatever income you made last year would be credited to debts incurred this year. This practice was so pervasive that thousands of workers never saw or received money, they would only receive promissory notes -VALES- from the landowners, who were often the same owners of the stores. That is why, 10-12 year-old boys went off to work in the fields, while girls in the same age group became maids.

My grandfather was among the fortunate few, because, as an orderly in the United Fruit Company's hospital, he had a year round job paying 50 cents per day.

There were always people sitting in my backyard, waiting for Georgy to get off his job. Some suffered from diarrhea, vomiting, fever or any sort of injuries. He would cleanse their wounds or give them medication he stored in a coffin-like cabinet he kept in his bedroom. As I pieced these events together, I concluded that this honorable man, who preached values to us, was forced by the brutal society in which he lived, to steal from his workplace, in order to serve those who were deprived of the most basic means of survival.

What can we say about the psychological trauma endured by unfortunate mothers, trapped in abusive relations, domestic violence and occasional life threatening situations without anywhere to go, forced to live this hazardous existence as the only means of feeding their hungry children.

For these and so many other reasons, none of us had to flock to South Africa to see what Apartheid was all about. We were born, lived and many died in our own Soweto! (AfroCubaWeb.com)

It was the Cuba of this era that many older Cubans in Miami remember so fondly with such deep nostalgia.I often wonder as I sit in a restaurant or a church in Miami surrounded by elderly Cubans who were at or near adulthood when they left the island in the late 1950's and early 1960's how different they are from white Southerners in this country of the same generation - especially when the similarities are so apparent.

No comments:

Post a Comment